U.S. state

"Texan" redirects here. For other uses, see Texas (disambiguation) and Texan (disambiguation).

State in the United States

|

Texas

|

Flag

Seal

|

| Nickname:

The Lone Star State

|

| Motto:

Friendship

|

| Anthem: "Texas, Our Texas" |

Location of Texas within the United States

|

| Country |

United States |

| Before statehood |

Republic of Texas |

| Admitted to the Union |

December 29, 1845 (28th) |

| Capital |

Austin |

| Largest city |

Houston |

| Largest county or equivalent |

Harris |

| Largest metro and urban areas |

Dallas–Fort Worth |

| • Governor |

Greg Abbott (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor |

Dan Patrick (R) |

| Legislature |

Texas Legislature |

| • Upper house |

Senate |

| • Lower house |

House of Representatives |

| Judiciary |

Supreme Court of Texas (Civil)

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (Criminal) |

| U.S. senators |

John Cornyn (R)

Ted Cruz (R) |

| U.S. House delegation |

25 Republicans

13 Democrats (list) |

|

• Total

|

268,596[1] sq mi (695,662 km2) |

| • Land |

261,232[1] sq mi (676,587 km2) |

| • Water |

7,365[1] sq mi (19,075 km2) 2.7% |

| • Rank |

2nd |

| • Length |

801[2] mi (1,289 km) |

| • Width |

773[2] mi (1,244 km) |

| Elevation

|

1,700 ft (520 m) |

| Highest elevation

(Guadalupe Peak[3][4][a])

|

8,751 ft (2,667.4 m) |

| Lowest elevation

(Gulf of Mexico[4])

|

0 ft (0 m) |

|

• Total

|

31,290,831[5] 31,290,831[5] |

| • Rank |

2nd |

| • Density |

114/sq mi (42.9/km2) |

| • Rank |

23rd |

| • Median household income

|

$75,800 (2023)[6] |

| • Income rank

|

23rd |

| Demonym(s) |

Texan

Texian (archaic)

Tejano (usually only used for Hispanics) |

| • Official language |

None |

| • Spoken language |

- English only: 64.9%

- Spanish: 28.8%[7]

- Other: 6.3%

|

| Majority of state |

UTC−06:00 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) |

UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| El Paso, Hudspeth, and northwestern Culberson counties |

UTC−07:00 (Mountain) |

| • Summer (DST) |

UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| USPS abbreviation |

TX

|

| ISO 3166 code |

US-TX |

| Traditional abbreviation |

Tex. |

| Latitude |

25°50′ N to 36°30′ N |

| Longitude |

93°31′ W to 106°39′ W |

| Website |

texas.gov |

State symbols of Texas

| List of state symbols |

Flag of Texas

|

Seal of Texas

|

| Slogan |

The Friendly State |

| Bird |

Northern mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) |

| Fish |

Guadalupe bass (Micropterus treculii) |

| Flower |

Bluebonnet (Lupinus spp., namely Texas bluebonnet, L. texensis) |

| Insect |

Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) |

| Mammal |

Texas longhorn, nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) |

| Mushroom |

Texas star (Chorioactis geaster) |

| Reptile |

Texas horned lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum) |

| Tree |

Pecan (Carya illinoinensis) |

| Food |

Chili |

| Game |

Texas 42 dominoes |

| Instrument |

Guitar |

| Shell |

Lightning whelk (Busycon perversum pulleyi) |

| Ship |

USS Texas |

| Soil |

Houston Black |

| Sport |

Rodeo |

| Other |

Molecule: Buckyball (For more, see article) |

|

Released in 2004

|

| Lists of United States state symbols |

Texas ( TEK-səss, TEK-siz;[8] Spanish: Texas or Tejas,[b]

pronounced [ˈtexas]) is the most populous state in the South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the west, and an international border with the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas to the south and southwest. Texas has a coastline on the Gulf of Mexico to the southeast. Covering 268,596 square miles (695,660 km2), and with over 31 million residents as of 2024,[5] it is the second-largest state by both area and population. Texas is nicknamed the Lone Star State for its former status as an independent republic, the Republic of Texas.[10]

Spain was the first European country to claim and control Texas. Following a short-lived colony controlled by France, Mexico controlled the land until 1836 when Texas won its independence, becoming the Republic of Texas. In 1845, Texas joined the United States of America as the 28th state.[11] The state's annexation set off a chain of events that led to the Mexican–American War in 1846. Following victory by the United States, Texas remained a slave state until the American Civil War, when it declared its secession from the Union in early 1861 before officially joining the Confederate States of America on March 2. After the Civil War and the restoration of its representation in the federal government, Texas entered a long period of economic stagnation.

Historically, five major industries shaped the Texas economy prior to World War II: cattle, bison, cotton, timber, and oil.[12] Before and after the Civil War, the cattle industry—which Texas came to dominate—was a major economic driver and created the traditional image of the Texas cowboy. In the later 19th century, cotton and lumber grew to be major industries as the cattle industry became less lucrative. Ultimately, the discovery of major petroleum deposits (Spindletop in particular) initiated an economic boom that became the driving force behind the economy for much of the 20th century. Texas developed a diversified economy and high tech industry during the mid-20th century. As of 2024[update], it has the second-highest number (52) of Fortune 500 companies headquartered in the United States. With a growing base of industry, the state leads in many industries, including tourism, agriculture, petrochemicals, energy, computers and electronics, aerospace, and biomedical sciences. Texas has led the U.S. in state export revenue since 2002 and has the second-highest gross state product.

The Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex and Greater Houston areas are the nation's fourth and fifth-most populous urban regions respectively. Its capital city is Austin. Due to its size and geologic features such as the Balcones Fault, Texas contains diverse landscapes common to both the U.S. Southern and the Southwestern regions.[13] Most population centers are in areas of former prairies, grasslands, forests, and the coastline. Traveling from east to west, terrain ranges from coastal swamps and piney woods, to rolling plains and rugged hills, to the desert and mountains of the Big Bend.

Etymology

[edit]

The name Texas, based on the Caddo word táy:shaʼ (/tÉ™ÌÂÂÂÂÂÂÂjËÂÂÂÂÂÂÂʃaÊâ€ÂÂÂÂÂÂ/) 'friend', was applied, in the spelling Tejas or Texas,[14][15][16][1] by the Spanish to the Caddo themselves, specifically the Hasinai Confederacy.[17]

During Spanish colonial rule, in the 18th century, the area was known as Nuevas Filipinas ('New Philippines') and Nuevo Reino de Filipinas ('New Kingdom of the Philippines'),[18] or as provincia de los Tejas ('province of the Tejas'),[19] later also provincia de Texas (or de Tejas), ('province of Texas').[20][18] It was incorporated as provincia de Texas into the Mexican Empire in 1821, and declared a republic in 1836. The Royal Spanish Academy recognizes both spellings, Tejas and Texas, as Spanish-language forms of the name.[21]

The English pronunciation with /ks/ is unetymological, contrary to the historical value of the letter x (/ʃ/) in Spanish orthography. Alternative etymologies of the name advanced in the late 19th century connected the name Texas with the Spanish word teja, meaning 'roof tile', the plural tejas being used to designate Indigenous Pueblo settlements.[22] A 1760s map by Jacques-Nicolas Bellin shows a village named Teijas on the Trinity River, close to the site of modern Crockett.[22]

History

[edit]

[edit]

Main article: History of Texas

Further information: Pre-Columbian Mexico and Native American tribes in Texas

Early Native American tribal territories

Early Native American tribal territories

Texas lies between two major cultural spheres of Pre-Columbian North America: the Southwestern and the Plains areas. Archaeologists have found that three major Indigenous cultures lived in this territory, and reached their developmental peak before the first European contact. These were:[23] the Ancestral Puebloans from the upper Rio Grande region, centered west of Texas; the Mississippian culture, also known as Mound Builders, which extended along the Mississippi River Valley east of Texas; and the civilizations of Mesoamerica, which were centered south of Texas. Influence of Teotihuacan in northern Mexico peaked around AD 500 and declined between the 8th and 10th centuries.

When Europeans arrived in the Texas region, the language families present in the state were Caddoan, Atakapan, Athabaskan, Coahuiltecan, and Uto-Aztecan, in addition to several language isolates such as Tonkawa. Uto-Aztecan Puebloan and Jumano peoples lived neared the Rio Grande in the western portion of the state and the Athabaskan-speaking Apache tribes lived throughout the interior. The agricultural, mound-building Caddo controlled much of the northeastern part of the state, along the Red, Sabine, and Neches River basins.[24][25] Atakapan peoples such as the Akokisa and Bidai lived along the northeastern Gulf Coast; the Karankawa lived along the central coast.[26] At least one tribe of Coahuiltecans, the Aranama, lived in southern Texas. This entire culture group, primarily centered in northeastern Mexico, is now extinct.

No culture was dominant across all of present-day Texas, and many peoples inhabited the area.[27] Native American tribes who have lived inside the boundaries of present-day Texas include the Alabama, Apache, Atakapan, Bidai, Caddo, Aranama, Comanche, Choctaw, Coushatta, Hasinai, Jumano, Karankawa, Kickapoo, Kiowa, Tonkawa, and Wichita.[28][29] Many of these peoples migrated from the north or east during the colonial period, such as the Choctaw, Alabama-Coushatta, and Delaware.[24]

The region was primarily controlled by the Spanish until the Texas Revolution. They were most interested in relationships with the Caddo, who were—like the Spanish—a settled, agricultural people. Several Spanish missions were opened in Caddo territory, but a lack of interest in Christianity among the Caddo meant that few were converted. Positioned between French Louisiana and Spanish Texas, the Caddo maintained relations with both, but were closer with the French.[30] After Spain took control of Louisiana, most of the missions in eastern Texas were closed and abandoned.[31] The United States obtained Louisiana following the 1803 Louisiana Purchase and began convincing tribes to self-segregate from whites by moving west; facing an overflow of native peoples in Missouri and Arkansas, they were able to negotiate with the Caddo to allow several displaced peoples to settle on unused lands in eastern Texas. These included the Muscogee, Houma Choctaw, Lenape and Mingo Seneca, among others, who came to view the Caddoans as saviors.[32][33]

The temperament of Native American tribes affected the fates of European explorers and settlers in that land.[34] Friendly tribes taught newcomers how to grow local crops, prepare foods, and hunt wild game. Warlike tribes resisted the settlers.[34] Prior treaties with the Spanish forbade either side from militarizing its native population in any potential conflict between the two nations. Several outbreaks of violence between Native Americans and Texans started to spread in the prelude to the Texas Revolution. Texans accused tribes of stealing livestock. While no proof was found,[24] those in charge of Texas at the time attempted to publicly blame and punish the Caddo, with the U.S. government trying to keep them in check. The Caddo never turned to violence because of the situation, except in cases of self-defense.[32]

By the 1830s, the U.S. had drafted the Indian Removal Act, which was used to facilitate the Trail of Tears. Fearing retribution, Indian Agents all over the eastern U.S. tried to convince all Indigenous peoples to uproot and move west. This included the Caddo of Louisiana and Arkansas. Following the Texas Revolution, the Texans chose to make peace with the Indigenous people, but did not honor former land claims or agreements.[citation needed] The first president of Texas, Sam Houston, aimed to cooperate and make peace with Native tribes, but his successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar, took a much more hostile stance. Hostility towards Natives by white Texans prompted the movement of most Native populations north into what would become Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma).[24][32] Only the Alabama-Coushatta would remain in the parts of Texas subject to white settlement, though the Comanche would continue to control most of the western half of the state until their defeat in the 1870s and 1880s.[35]

Colonization

[edit]

Main articles: New Spain, New France, Louisiana (New France), French colonization of Texas, Spanish Texas, French and Indian War, Treaty of Paris (1763), Seminole Wars, Adams–Onís Treaty, Mexican War of Independence, Treaty of Córdoba, First Mexican Empire, Mexican Texas, Provisional Government of Mexico (1823–24), 1824 Constitution of Mexico, First Mexican Republic, Siete Leyes, and Centralist Republic of Mexico

The first historical document related to Texas was a map of the Gulf Coast, created in 1519 by Spanish explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda.[36] Nine years later, shipwrecked Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his cohort became the first Europeans in what is now Texas.[37][38] Cabeza de Vaca reported that in 1528, when the Spanish landed in the area, "half the natives died from a disease of the bowels and blamed us."[39] Cabeza de Vaca also made observations about the way of life of the Ignaces Natives of Texas.[c][41] Francisco Vázquez de Coronado described another encounter with native people in 1541.[d][43]

The expedition of Hernando de Soto entered into Texas from the east, seeking a route to Mexico. They passed through the Caddo lands but turned back after reaching the River of Daycao (possibly the Brazos or Colorado), beyond which point the Native peoples were nomadic and did not have the agricultural stores to feed the expedition.[44][45]

European powers ignored the area until accidentally settling there in 1685. Miscalculations by René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle resulted in his establishing the colony of Fort Saint Louis at Matagorda Bay rather than along the Mississippi River. The colony lasted only four years before succumbing to harsh conditions and hostile natives. A small band of survivors traveled eastward into the lands of the Caddo, but La Salle was killed by disgruntled expedition members.[48]

In 1690 Spanish authorities, concerned that France posed a competitive threat, constructed several missions in East Texas among the Caddo. After Caddo resistance, the Spanish missionaries returned to Mexico. When France began settling Louisiana, in 1716 Spanish authorities responded by founding a new series of missions in East Texas.[51] Two years later, they created San Antonio as the first Spanish civilian settlement in the area.

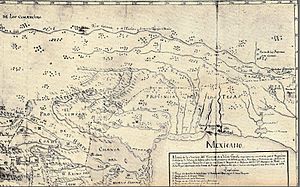

Nicolas de La Fora's 1771 map of the northern frontier of New Spain clearly shows the Provincia de los Tejas.[53]

Nicolas de La Fora's 1771 map of the northern frontier of New Spain clearly shows the Provincia de los Tejas.[53]

Hostile native tribes and distance from nearby Spanish colonies discouraged settlers from moving to the area. It was one of New Spain's least populated provinces. In 1749, the Spanish peace treaty with the Lipan Apache angered many tribes, including the Comanche, Tonkawa, and Hasinai. The Comanche signed a treaty with Spain in 1785 and later helped to defeat the Lipan Apache and Karankawa tribes.[57] With numerous missions being established, priests led a peaceful conversion of most tribes. By the end of the 18th century only a few nomadic tribes had not converted.

Stephen F. Austin was the first American empresario given permission to operate a colony within Mexican Texas.

Stephen F. Austin was the first American empresario given permission to operate a colony within Mexican Texas.

Mexico in 1824. Coahuila y Tejas is the northeasternmost state.

Mexico in 1824. Coahuila y Tejas is the northeasternmost state.

When the United States purchased Louisiana from France in 1803, American authorities insisted the agreement also included Texas. The boundary between New Spain and the United States was finally set in 1819 at the Sabine River, the modern border between Texas and Louisiana. Eager for new land, many U.S. settlers refused to recognize the agreement. Several filibusters raised armies to invade the area west of the Sabine River. Marked by the War of 1812, some men who had escaped from the Spanish, held (Old) Philippines had immigrated to and also passed through Texas (New Philippines)[62] and reached Louisiana where Philippine exiles aided the United States in the defense of New Orleans against a British invasion, with Filipinos in the Saint Malo settlement assisting Jean Lafitte in the Battle of New Orleans.[63]

In 1821, the Mexican War of Independence included the Texas territory, which became part of Mexico. Due to its low population, the territory was assigned to other states and territories of Mexico; the core territory was part of the state of Coahuila y Tejas, but other parts of today's Texas were part of Tamaulipas, Chihuahua, or the Mexican Territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo México.

Hoping more settlers would reduce the near-constant Comanche raids, Mexican Texas liberalized its immigration policies to permit immigrants from outside Mexico and Spain. Large swathes of land were allotted to empresarios, who recruited settlers from the United States, Europe, and the Mexican interior, primarily the U.S. Austin's settlers, the Old Three Hundred, made places along the Brazos River in 1822. The population of Texas grew rapidly. In 1825, Texas had about 3,500 people, with most of Mexican descent. By 1834, the population had grown to about 37,800 people, with only 7,800 of Mexican descent.

Many immigrants openly flouted Mexican law, especially the prohibition against slavery. Combined with United States' attempts to purchase Texas, Mexican authorities decided in 1830 to prohibit continued immigration from the United States. However, illegal immigration from the United States into Mexico continued to increase the population of Texas. New laws also called for the enforcement of customs duties angering native Mexican citizens (Tejanos) and recent immigrants alike. The Anahuac Disturbances in 1832 were the first open revolt against Mexican rule, coinciding with a revolt in Mexico against the nation's president. Texians sided with the federalists against the government and drove all Mexican soldiers out of East Texas. They took advantage of the lack of oversight to agitate for more political freedom. Texians met at the Convention of 1832 to discuss requesting independent statehood, among other issues. The following year, Texians reiterated their demands at the Convention of 1833.[76]

Republic

[edit]

Main articles: Texas Revolution, Convention of 1836, Texas Declaration of Independence, Treaties of Velasco, and Republic of Texas

Within Mexico, tensions continued between federalists and centralists. In early 1835, wary Texians formed Committees of Correspondence and Safety.[77] The unrest erupted into armed conflict in late 1835 at the Battle of Gonzales. This launched the Texas Revolution. Texians elected delegates to the Consultation, which created a provisional government. The provisional government soon collapsed from infighting, and Texas was without clear governance for the first two months of 1836.[80]

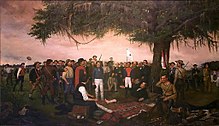

Surrender of Santa Anna. Painting by William Henry Huddle, 1886.

Surrender of Santa Anna. Painting by William Henry Huddle, 1886.

Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna personally led an army to end the revolt. General José de Urrea defeated all the Texian resistance along the coast culminating in the Goliad massacre.[82] López de Santa Anna's forces, after a thirteen-day siege, overwhelmed Texian defenders at the Battle of the Alamo. News of the defeats sparked panic among Texas settlers.

The Republic of Texas with present-day borders superimposed

The Republic of Texas with present-day borders superimposed

The newly elected Texian delegates to the Convention of 1836 quickly signed a declaration of independence on March 2, forming the Republic of Texas. After electing interim officers, the Convention disbanded.[84] The new government joined the other settlers in Texas in the Runaway Scrape, fleeing from the approaching Mexican army.

After several weeks of retreat, the Texian Army commanded by Sam Houston attacked and defeated López de Santa Anna's forces at the Battle of San Jacinto. López de Santa Anna was captured and forced to sign the Treaties of Velasco, ending the war. The Constitution of the Republic of Texas prohibited the government from restricting slavery or freeing slaves, and required free people of African descent to leave the country.[87]

Political battles raged between two factions of the new Republic. The nationalist faction, led by Mirabeau B. Lamar, advocated the continued independence of Texas, the expulsion of the Native Americans, and the expansion of the Republic to the Pacific Ocean. Their opponents, led by Sam Houston, advocated the annexation of Texas to the United States and peaceful co-existence with Native Americans. The conflict between the factions was typified by an incident known as the Texas Archive War.[88] With wide popular support, Texas first applied for annexation to the United States in 1836, but its status as a slaveholding country caused its admission to be controversial and it was initially rebuffed. This status, and Mexican diplomacy in support of its claims to the territory, also complicated Texas's ability to form foreign alliances and trade relationships.[89]

The Comanche Indians furnished the main Native American opposition to the Texas Republic, manifested in multiple raids on settlements.[90] Mexico launched two small expeditions into Texas in 1842. The town of San Antonio was captured twice and Texans were defeated in battle in the Dawson massacre. Despite these successes, Mexico did not keep an occupying force in Texas, and the republic survived.[91] The cotton price crash of the 1840s depressed the country's economy.[89]

Statehood

[edit]

Main article: History of Texas (1845–1860)

Further information: Texas annexation, Admission to the Union, Mexican–American War, and Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

See also: List of U.S. states by date of admission to the Union

On March 2, 1936, the U.S. Post Office issued a commemorative stamp commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Texas Declaration of Independence, featuring Sam Houston (left), Stephen Austin and the Alamo.

On March 2, 1936, the U.S. Post Office issued a commemorative stamp commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Texas Declaration of Independence, featuring Sam Houston (left), Stephen Austin and the Alamo.

Texas was finally annexed when the expansionist James K. Polk won the election of 1844.[92] On December 29, 1845, the U.S. Congress admitted Texas to the U.S.[93] After Texas's annexation, Mexico broke diplomatic relations with the United States. While the United States claimed Texas's border stretched to the Rio Grande, Mexico claimed it was the Nueces River leaving the Rio Grande Valley under contested Texan sovereignty.[93] While the former Republic of Texas could not enforce its border claims, the United States had the military strength and the political will to do so. President Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor south to the Rio Grande on January 13, 1846. A few months later Mexican troops routed an American cavalry patrol in the disputed area in the Thornton Affair starting the Mexican–American War. The first battles of the war were fought in Texas: the Siege of Fort Texas, Battle of Palo Alto and Battle of Resaca de la Palma. After these decisive victories, the United States invaded Mexican territory, ending the fighting in Texas.[94]

Captain Charles A. May's squadron of the 2nd Dragoons slashes through the Mexican Army lines. Resaca de la Palma, Texas, May 1846.

Captain Charles A. May's squadron of the 2nd Dragoons slashes through the Mexican Army lines. Resaca de la Palma, Texas, May 1846.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the two-year war. In return for US$18,250,000, Mexico gave the U.S. undisputed control of Texas, ceded the Mexican Cession in 1848, most of which today is called the American Southwest, and Texas's borders were established at the Rio Grande.[94]

The Compromise of 1850 set Texas's boundaries at their present position: Texas ceded its claims to land which later became half of present-day New Mexico,[95] a third of Colorado, and small portions of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming to the federal government, in return for the assumption of $10 million of the old republic's debt.[95] Post-war Texas grew rapidly as migrants poured into the cotton lands of the state.[96] They also brought or purchased enslaved African Americans, whose numbers tripled in the state from 1850 to 1860, from 58,000 to 182,566.[97]

Civil War to late 19th century

[edit]

Main article: History of Texas (1865–1899)

Further information: Ordinance of Secession, Confederate States of America, and Texas in the American Civil War

Texas re-entered war following the election of 1860. During this time, Black people comprised 30 percent of the state's population, and they were overwhelmingly enslaved.[98] When Abraham Lincoln was elected, South Carolina seceded from the Union; five other Deep South states quickly followed. A state convention considering secession opened in Austin on January 28, 1861. On February 1, by a vote of 166–8, the convention adopted an Ordinance of Secession. Texas voters approved this Ordinance on February 23, 1861. Texas joined the newly created Confederate States of America on March 4, 1861, ratifying the permanent C.S. Constitution on March 23.[1][99]

Not all Texans favored secession initially, although many of the same would later support the Southern cause. Texas's most notable Unionist was the state governor, Sam Houston. Not wanting to aggravate the situation, Houston refused two offers from President Lincoln for Union troops to keep him in office. After refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy, Houston was deposed.[100]

While far from the major battlefields of the American Civil War, Texas contributed large numbers of soldiers and equipment.[101] Union troops briefly occupied the state's primary port, Galveston. Texas's border with Mexico was known as the "backdoor of the Confederacy" because trade occurred at the border, bypassing the Union blockade.[102] The Confederacy repulsed all Union attempts to shut down this route,[101] but Texas's role as a supply state was marginalized in mid-1863 after the Union capture of the Mississippi River. The final battle of the Civil War was fought at Palmito Ranch, near Brownsville, Texas, and saw a Confederate victory.[103][104]

Texas descended into anarchy for two months between the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia and the assumption of authority by Union General Gordon Granger. Violence marked the early months of Reconstruction.[101] Juneteenth commemorates the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in Galveston by General Gordon Granger, almost two and a half years after the original announcement.[105][106] President Johnson, in 1866, declared the civilian government restored in Texas.[107] Despite not meeting Reconstruction requirements, Congress resumed allowing elected Texas representatives into the federal government in 1870. Social volatility continued as the state struggled with agricultural depression and labor issues.[108]

Like most of the South, the Texas economy was devastated by the War. However, since the state had not been as dependent on slaves as other parts of the South, it was able to recover more quickly. The culture in Texas during the later 19th century exhibited many facets of a frontier territory. The state became notorious as a haven for people from other parts of the country who wanted to escape debt, war tensions, or other problems. "Gone to Texas" was a common expression for those fleeing the law in other states. Nevertheless, the state also attracted many businessmen and other settlers with more legitimate interests.[109]

The cattle industry continued to thrive, though it gradually became less profitable. Cotton and lumber became major industries creating new economic booms in various regions. Railroad networks grew rapidly as did the port at Galveston as commerce expanded. The lumber industry quickly expanded and was Texas' largest industry prior to the 20th century.[110]

Early to mid-20th century

[edit]

Spindletop, the first major oil gusher

Spindletop, the first major oil gusher

In 1900, Texas suffered the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history during the Galveston hurricane.[111] On January 10, 1901, the first major oil well in Texas, Spindletop, was found south of Beaumont. Other fields were later discovered nearby in East Texas, West Texas, and under the Gulf of Mexico. The resulting "oil boom" transformed Texas.[112] Oil production averaged three million barrels per day at its peak in 1972.[113]

In 1901, the Democratic-dominated state legislature passed a bill requiring payment of a poll tax for voting, which effectively disenfranchised most Black and many poor White and Latino people. In addition, the legislature established white primaries, ensuring minorities were excluded from the formal political process. The number of voters dropped dramatically, and the Democrats crushed competition from the Republican and Populist parties.[114][115] The Socialist Party became the second-largest party in Texas after 1912,[116] coinciding with a large socialist upsurge in the United States during fierce battles in the labor movement and the popularity of national heroes like Eugene V. Debs. The socialists' popularity soon waned after their vilification by the federal government for their opposition to U.S. involvement in World War I.[117][118]

The Great Depression and the Dust Bowl dealt a double blow to the state's economy, which had significantly improved since the Civil War. Migrants abandoned the worst-hit sections of Texas during the Dust Bowl years. Especially from this period on, Black people left Texas in the Great Migration to get work in the Northern United States or California and to escape segregation.[98] In 1940, Texas was 74% White, 14.4% Black, and 11.5% Hispanic.[119]

World War II had a dramatic impact on Texas, as federal money poured in to build military bases, munitions factories, detention camps and Army hospitals; 750,000 Texans left for service; the cities exploded with new industry; and hundreds of thousands of poor farmers left the fields for much better-paying war jobs, never to return to agriculture.[120][121] Texas manufactured 3.1 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking eleventh among the 48 states.[122]

Texas modernized and expanded its system of higher education through the 1960s. The state created a comprehensive plan for higher education, funded in large part by oil revenues, and a central state apparatus designed to manage state institutions more efficiently. These changes helped Texas universities receive federal research funds.[123]

Mid-20th to early 21st century

[edit]

Beginning around the mid-20th century, Texas began to transform from a rural and agricultural state to one urban and industrialized.[124] The state's population grew quickly during this period, with large levels of migration from outside the state.[124] As a part of the Sun Belt, Texas experienced strong economic growth, particularly during the 1970s and early 1980s.[124] Texas's economy diversified, lessening its reliance on the petroleum industry.[124] By 1990, Hispanics and Latino Americans overtook Blacks to become the largest minority group.[124] Texas has the largest Black population with over 3.9 million.[125]

During the late 20th century, the Republican Party replaced the Democratic Party as the dominant party in the state.[124] Beginning in the early 21st century, metropolitan areas including Dallas–Fort Worth and Greater Austin became centers for the Texas Democratic Party in statewide and national elections as liberal policies became more accepted in urban areas.[126][127][128][129]

From the mid-2000s to 2019, Texas gained an influx of business relocations and regional headquarters from companies in California.[130][131][132][133] Texas became a major destination for migration during the early 21st century and was named the most popular state to move for three consecutive years.[134] Another study in 2019 determined Texas's growth rate at 1,000 people per day.[135]

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Texas, the first confirmed case of the virus in Texas was announced on March 4, 2020.[136] On April 27, 2020, Governor Greg Abbott announced phase one of re-opening the economy.[137] Amid a rise in COVID-19 cases in autumn 2020, Abbott refused to enact further lockdowns.[138][139] In November 2020, Texas was selected as one of four states to test Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine distribution.[140] As of February 2, 2021, there had been over 2.4 million confirmed cases in Texas, with at least 37,417 deaths.[141]

During February 13–17, 2021, the state faced a major weather emergency as Winter Storm Uri hit the state, as well as most of the Southeastern and Midwestern United States.[142][143] Historically high power usage across the state caused the state's power grid to become overworked and ERCOT (the main operator of the Texas Interconnection grid) declared an emergency and began to implement rolling blackouts across Texas, causing a power crisis.[144][145][146] Over 3 million Texans were without power and over 4 million were under boil-water notices.[147]

Geography

[edit]

Main article: Geography of Texas

Sam Rayburn Reservoir

Sam Rayburn Reservoir

Texas Hill Country

Texas Hill Country

Texas is the second-largest U.S. state by area, after Alaska, and the largest state within the contiguous United States, at 268,820 square miles (696,200 km2). If it were an independent country, Texas would be the 39th-largest.[148] It ranks 26th worldwide amongst country subdivisions by size.

Texas is in the south central part of the United States. The Rio Grande forms a natural border with the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas to the south. The Red River forms a natural border with Oklahoma and Arkansas to the north. The Sabine River forms a natural border with Louisiana to the east. The Texas Panhandle has an eastern border with Oklahoma at 100° W, a northern border with Oklahoma at 36°30' N and a western border with New Mexico at 103° W. El Paso lies on the state's western tip at 32° N and the Rio Grande.[95]

With 10 climatic regions, 14 soil regions and 11 distinct ecological regions, regional classification becomes complicated with differences in soils, topography, geology, rainfall, and plant and animal communities.[149] One classification system divides Texas, in order from southeast to west, into the following: Gulf Coastal Plains, Interior Lowlands, Great Plains, and Basin and Range Province.[150]

The Gulf Coastal Plains region wraps around the Gulf of Mexico on the southeast section of the state. Vegetation in this region consists of thick piney woods. The Interior Lowlands region consists of gently rolling to hilly forested land and is part of a larger pine-hardwood forest. The Cross Timbers region and Caprock Escarpment are part of the Interior Lowlands.[150]

Steinhagen Reservoir

Steinhagen Reservoir

The Great Plains region in Central Texas spans through the state's panhandle and Llano Estacado to the state's hill country near Lago Vista and Austin. This region is dominated by prairie and steppe. "Far West Texas" or the "Trans-Pecos" region is the state's Basin and Range Province. The most varied of the regions, this area includes Sand Hills, the Stockton Plateau, desert valleys, wooded mountain slopes and desert grasslands.[151]

Texas has 3,700 named streams and 15 major rivers,[152][153] with the Rio Grande as the largest. Other major rivers include the Pecos, the Brazos, Colorado, and Red River. While Texas has few natural lakes, Texans have built more than a hundred artificial reservoirs.[154]

The size and unique history of Texas make its regional affiliation debatable; it can be considered a Southern or a Southwestern state, or both. The vast geographic, economic, and cultural diversity within the state itself prohibits easy categorization of the whole state into a recognized region of the United States. Notable extremes range from East Texas which is often considered an extension of the Deep South, to Far West Texas which is generally acknowledged to be part of the interior Southwest.[155]

Geology

[edit]

Main article: Geology of Texas

Palo Duro Canyon

Palo Duro Canyon

Franklin Mountains State Park

Franklin Mountains State Park

Big Bend National Park

Big Bend National Park

Texas is the southernmost part of the Great Plains, which ends in the south against the folded Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico. The continental crust forms a stable Mesoproterozoic craton which changes across a broad continental margin and transitional crust into true oceanic crust of the Gulf of Mexico. The oldest rocks in Texas date from the Mesoproterozoic and are about 1,600 million years old.[156]

This margin existed until Laurasia and Gondwana collided in the Pennsylvanian subperiod to form Pangea.[157] Pangea began to break up in the Triassic, but seafloor spreading to form the Gulf of Mexico occurred only in the mid- and late Jurassic. The shoreline shifted again to the eastern margin of the state and the Gulf of Mexico's passive margin began to form. Today 9 to 12 miles (14 to 19 km) of sediments are buried beneath the Texas continental shelf and a large proportion of remaining US oil reserves are here. The incipient Gulf of Mexico basin was restricted and seawater often evaporated completely to form thick evaporite deposits of Jurassic age. These salt deposits formed salt dome diapirs, and are found in East Texas along the Gulf coast.[158]

East Texas outcrops consist of Cretaceous and Paleogene sediments which contain important deposits of Eocene lignite. The Mississippian and Pennsylvanian sediments in the north; Permian sediments in the west; and Cretaceous sediments in the east, along the Gulf coast and out on the Texas continental shelf contain oil. Oligocene volcanic rocks are found in far west Texas in the Big Bend area. A blanket of Miocene sediments known as the Ogallala formation in the western high plains region is an important aquifer.[159] Located far from an active plate tectonic boundary, Texas has no volcanoes and few earthquakes.[160]

Wildlife

[edit]

See also: List of mammals of Texas, List of birds of Texas, List of reptiles of Texas, and List of amphibians of Texas

Texas is the home to 65 species of mammals, 213 species of reptiles and amphibians, including the American green tree frog, and the greatest diversity of bird life in the United States—590 native species in all.[161] At least 12 species have been introduced and now reproduce freely in Texas.[162]

Texas plays host to several species of wasps, including an abundance of Polistes exclamans,[163] and is an important ground for the study of Polistes annularis.[164]

During the spring Texas wildflowers such as the state flower, the bluebonnet, line highways throughout Texas. During the Johnson Administration the first lady, Lady Bird Johnson, worked to draw attention to Texas wildflowers.[165]

Climate

[edit]

Main article: Climate of Texas

Köppen climate types in Texas

Köppen climate types in Texas

The large size of Texas and its location at the intersection of multiple climate zones gives the state highly variable weather. The Panhandle of the state has colder winters than North Texas, while the Gulf Coast has mild winters. Texas has wide variations in precipitation patterns. El Paso, on the western end of the state, averages 8.7 inches (220 mm) of annual rainfall,[166] while parts of southeast Texas average as much as 64 inches (1,600 mm) per year.[167] Dallas in the North Central region averages a more moderate 37 inches (940 mm) per year.[168]

Snow falls multiple times each winter in the Panhandle and mountainous areas of West Texas, once or twice a year in North Texas, and once every few years in Central and East Texas. Snow falls south of San Antonio or on the coast only in rare circumstances. Of note is the 2004 Christmas Eve snowstorm, when 6 inches (150 mm) of snow fell as far south as Kingsville, where the average high temperature in December is 65 °F.[169]

Night-time summer temperatures range from the upper 50s °F (14 °C) in the West Texas mountains to 80 °F (27 °C) in Galveston.[170][171]

The table below consists of averages for August (generally the warmest month) and January (generally the coldest) in selected cities in various regions of the state.

Average daily maximum and minimum temperatures for selected cities in Texas[172]

| Location |

August (°F) |

August (°C) |

January (°F) |

January (°C) |

| Houston |

94/75 |

34/24 |

63/54 |

17/12 |

| San Antonio |

96/74 |

35/23 |

63/40 |

17/5 |

| Dallas |

96/77 |

36/25 |

57/37 |

16/3 |

| Austin |

97/74 |

36/23 |

61/45 |

16/5 |

| El Paso |

92/67 |

33/21 |

57/32 |

14/0 |

| Laredo |

100/77 |

37/25 |

67/46 |

19/7 |

| Amarillo |

89/64 |

32/18 |

50/23 |

10/−4 |

| Brownsville |

94/76 |

34/24 |

70/51 |

21/11 |

Storms

[edit]

See also: List of Texas hurricanes

Thunderstorms strike Texas often, especially the eastern and northern portions of the state. Tornado Alley covers the northern section of Texas. The state experiences the most tornadoes in the United States, an average of 139 a year. These strike most frequently in North Texas and the Panhandle.[173] Tornadoes in Texas generally occur in April, May, and June.[174]

Some of the most destructive hurricanes in U.S. history have impacted Texas. A hurricane in 1875 killed about 400 people in Indianola, followed by another hurricane in 1886 that destroyed the town. These events allowed Galveston to take over as the chief port city. The 1900 Galveston hurricane subsequently devastated that city, killing about 8,000 people or possibly as many as 12,000 in the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history.[111] In 2017, Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Rockport as a Category 4 Hurricane, causing significant damage there. Its unprecedented amounts of rain over the Greater Houston area resulted in widespread and catastrophic flooding that inundated hundreds of thousands of homes. Harvey ultimately became the costliest hurricane worldwide, causing an estimated $198.6 billion in damage, surpassing the cost of Hurricane Katrina.[175]

Other devastating Texas hurricanes include the 1915 Galveston hurricane, Hurricane Audrey in 1957, Hurricane Carla in 1961, Hurricane Beulah in 1967, Hurricane Alicia in 1983, Hurricane Rita in 2005, and Hurricane Ike in 2008. Tropical storms have also caused their share of damage: Allison in 1989 and again during 2001, Claudette in 1979, and Tropical Storm Imelda in 2019.[176][177][178]

There is no substantial physical barrier between Texas and the polar region. Although it is unusual, it is possible for arctic or polar air masses to penetrate Texas,[179][180] as occurred during the February 13–17, 2021 North American winter storm.[181][182] Usually, prevailing winds in North America will push polar air masses to the southeast before they reach Texas. Because such intrusions are rare, and, perhaps, unexpected, they may result in crises such as the 2021 Texas power crisis.

Greenhouse gases

[edit]

Main article: Climate change in Texas

As of 2017[update], Texas emitted the most greenhouse gases in the U.S.[183] As of 2017[update] the state emits about 1,600 billion pounds (707 million metric tons) of carbon dioxide annually.[183] As an independent state, Texas would rank as the world's seventh-largest producer of greenhouse gases.[184] Causes of the state's vast greenhouse gas emissions include the state's large number of coal power plants and the state's refining and manufacturing industries.[184] In 2010, there were 2,553 "emission events" which poured 44.6 million pounds (20,200 metric tons) of contaminants into the Texas sky.[185]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

See also: List of counties in Texas, List of Texas metropolitan areas, and List of municipalities in Texas

| Largest city in Texas by year[186] |

| Year(s) |

City |

| 1850–1870 |

San Antonio[187] |

| 1870–1890 |

Galveston[188] |

| 1890–1900 |

Dallas[186] |

| 1900–1930 |

San Antonio[187] |

| 1930–present |

Houston[189] |

Colonia in the Rio Grande Valley near the Mexico–United States border

Colonia in the Rio Grande Valley near the Mexico–United States border

The state has three cities with populations exceeding one million: Houston, San Antonio, and Dallas.[190] These three rank among the 10 most populous cities of the United States. As of 2020, six Texas cities had populations greater than 600,000. Austin, Fort Worth, and El Paso are among the 20 largest U.S. cities. Texas has four metropolitan areas with populations greater than a million: Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington, Houston–Sugar Land–The Woodlands, San Antonio–New Braunfels, and Austin–Round Rock–San Marcos. The Dallas–Fort Worth and Houston metropolitan areas number about 7.5 million and 7 million residents as of 2019, respectively.[191]

Three interstate highways—I-35 to the west (Dallas–Fort Worth to San Antonio, with Austin in between), I-45 to the east (Dallas to Houston), and I-10 to the south (San Antonio to Houston) define the Texas Urban Triangle region. The region of 60,000 square miles (160,000 km2) contains most of the state's largest cities and metropolitan areas as well as 17 million people, nearly 75 percent of Texas's total population.[192] Houston and Dallas have been recognized as world cities.[193] These cities are spread out amongst the state.[194]

In contrast to the cities, unincorporated rural settlements known as colonias often lack basic infrastructure and are marked by poverty.[195] The office of the Texas Attorney General stated, in 2011, that Texas had about 2,294 colonias, and estimates about 500,000 lived in the colonias. Hidalgo County, as of 2011, has the largest number of colonias.[196] Texas has the largest number of people living in colonias of all states.[195]

Texas has 254 counties, more than any other state.[197] Each county runs on Commissioners' Court system consisting of four elected commissioners (one from each of four precincts in the county, roughly divided according to population) and a county judge elected at large from the entire county. County government runs similar to a "weak" mayor-council system; the county judge has no veto authority, but votes along with the other commissioners.[198][199]

Although Texas permits cities and counties to enter "interlocal agreements" to share services, the state does not allow consolidated city-county governments, nor does it have metropolitan governments. Counties are not granted home rule status; their powers are strictly defined by state law. The state does not have townships—areas within a county are either incorporated or unincorporated. Incorporated areas are part of a municipality. The county provides limited services to unincorporated areas and to some smaller incorporated areas. Municipalities are classified either "general law" cities or "home rule".[200] A municipality may elect home rule status once it exceeds 5,000 population with voter approval.[201]

Texas also permits the creation of "special districts", which provide limited services. The most common is the school district, but can also include hospital districts, community college districts, and utility districts. Municipal, school district, and special district elections are nonpartisan,[202] though the party affiliation of a candidate may be well-known. County and state elections are partisan.[203]

|

Largest cities or towns in Texas

2022 U.S. Census Bureau Estimate[204]

|

| |

Rank |

Name |

County |

Pop. |

Rank |

Name |

County |

Pop. |

|

Houston

San Antonio |

1 |

Houston |

Harris |

2,302,878 |

11 |

Laredo |

Webb |

256,187 |

Dallas

Austin |

| 2 |

San Antonio |

Bexar |

1,472,909 |

12 |

Irving |

Dallas |

254,715 |

| 3 |

Dallas |

Dallas |

1,299,544 |

13 |

Garland |

Dallas |

240,854 |

| 4 |

Austin |

Travis |

974,447 |

14 |

Frisco |

Collin |

219,587 |

| 5 |

Fort Worth |

Tarrant |

956,709 |

15 |

McKinney |

Collin |

207,507 |

| 6 |

El Paso |

El Paso |

677,456 |

16 |

Grand Prairie |

Dallas |

201,843 |

| 7 |

Arlington |

Tarrant |

394,602 |

17 |

Amarillo |

Potter |

201,291 |

| 8 |

Corpus Christi |

Nueces |

316,239 |

18 |

Brownsville |

Cameron |

189,382 |

| 9 |

Plano |

Collin |

289,547 |

19 |

Killeen |

Bell |

159,172 |

| 10 |

Lubbock |

Lubbock |

263,930 |

20 |

Denton |

Denton |

150,353 |

Demographics

[edit]

Main article: Demographics of Texas

Historical population

| Census |

Pop. |

Note |

%± |

| 1850 |

212,592 |

|

— |

| 1860 |

604,215 |

|

184.2% |

| 1870 |

818,579 |

|

35.5% |

| 1880 |

1,591,749 |

|

94.5% |

| 1890 |

2,235,527 |

|

40.4% |

| 1900 |

3,048,710 |

|

36.4% |

| 1910 |

3,896,542 |

|

27.8% |

| 1920 |

4,663,228 |

|

19.7% |

| 1930 |

5,824,715 |

|

24.9% |

| 1940 |

6,414,824 |

|

10.1% |

| 1950 |

7,711,194 |

|

20.2% |

| 1960 |

9,579,677 |

|

24.2% |

| 1970 |

11,196,730 |

|

16.9% |

| 1980 |

14,229,191 |

|

27.1% |

| 1990 |

16,986,510 |

|

19.4% |

| 2000 |

20,851,820 |

|

22.8% |

| 2010 |

25,145,561 |

|

20.6% |

| 2020 |

29,145,505 |

|

15.9% |

| 2024 (est.) |

31,290,831 |

[5] |

7.4% |

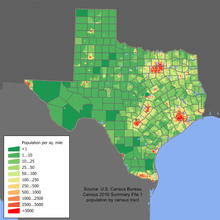

Texas population density map

Texas population density map

The resident population of Texas was 29,145,505 in the 2020 census, a 15.9% increase since the 2010 census.[205] At the 2020 census, the apportioned population of Texas stood at 29,183,290.[206] The U.S. Census Bureau estimated the population was 31,290,831 as of July 1, 2024, an increase of 7.4% since the 2020 census.[5] Texas is the second-most populous state in the United States after California and the only other U.S. state to surpass a total estimated population of 30 million people as of July 2, 2022.[207][208]

In 2015, Texas had 4.7 million foreign-born residents, about 17% of the population and 21.6% of the state workforce.[209] The major countries of origin for Texan immigrants were Mexico (55.1% of immigrants), India (5%), El Salvador (4.3%), Vietnam (3.7%), and China (2.3%).[209] Of immigrant residents, 35.8 percent were naturalized U.S. citizens.[209] As of 2018, the population increased to 4.9 million foreign-born residents or 17.2% of the state population, up from 2,899,642 in 2000.[210]

In 2014, there were an estimated 1.7 million undocumented immigrants in Texas, making up 35% of the total Texas immigrant population and 6.1% of the total state population.[209] In addition to the state's foreign-born population, an additional 4.1 million Texans (15% of the state's population) were born in the United States and had at least one immigrant parent.[209]

According to the American Community Survey's 2019 estimates, 1,739,000 residents were undocumented immigrants, a decrease of 103,000 since 2014 and increase of 142,000 since 2016. Of the undocumented immigrant population, 951,000 have resided in Texas from less than 5 up to 14 years. An estimated 788,000 lived in Texas from 15 to 19 and 20 years or more.[211]

Texas's Rio Grande Valley has seen significant migration from across the U.S.–Mexico border. During the 2014 crisis, many Central Americans, including unaccompanied minors traveling alone from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, reached the state, overwhelming Border Patrol resources for a time. Many sought asylum in the United States.[212][213]

Texas's population density as of 2010 is 96.3 people per square mile (37.2 people/km2) which is slightly higher than the average population density of the U.S. as a whole, at 87.4 people per square mile (33.7 people/km2). In contrast, while Texas and France are similarly sized geographically, the European country has a population density of 301.8 people per square mile (116.5 people/km2). Two-thirds of all Texans live in major metropolitan areas such as Houston.

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 24,432 homeless people in Texas.[214][215]

Race and ethnicity

[edit]

Map of counties in Texas by racial and ethnic plurality, per the 2020 U.S. census

Map of counties in Texas by racial and ethnic plurality, per the 2020 U.S. census

30–40%

40–50%

50–60%

60–70%

70–80%

80–90%

40–50%

50–60%

60–70%

70–80%

80–90%

90%+

| Non-Hispanic White

20–30%

|

Hispanic or Latino |

Ethnic composition as of the 2020 census

| Race and ethnicity[216] |

Alone |

Total |

| Hispanic or Latino[e] |

— |

|

40.2% |

40.2

|

| Non-Hispanic White |

39.7% |

39.7

|

39.8% |

39.8

|

| African American |

11.8% |

11.8

|

12.8% |

12.8

|

| Asian |

5.4% |

5.4

|

6.1% |

6.1

|

| Native American |

0.3% |

0.3

|

1.4% |

1.4

|

| Pacific Islander |

0.1% |

0.1

|

0.2% |

0.2

|

| Other |

0.4% |

0.4

|

1.0% |

1

|

In 2019, non-Hispanic Whites represented 41.2% of Texas's population, reflecting a national demographic shift.[217][218][219] Black people made up 12.9%, American Indians and Alaska Natives 1.0%, Asian Americans 5.2%, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders 0.1%, some other race 0.2%, and two or more races 1.8%. Hispanics or Latino Americans of any race made up 39.7% of the estimated population.[220]

At the 2020 census, the racial and ethnic composition of the state was 42.5% White (39.8% non-Hispanic White), 11.8% Black, 5.4% Asian, 0.3% American Indian and Alaska Native, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, 13.6% some other race, 17.6% two or more races, and 40.2% Hispanic and Latino American of any race.[221][222]

In 2010, 49% of all births were Hispanics; 35% were non-Hispanic White; 11.5% were non-Hispanic Black, and 4.3% were Asians/Pacific Islanders.[223] Based on U.S. Census Bureau data released in February 2011, for the first time in recent history, Texas's White population is below 50% (45%) and Hispanics grew to 38%. Between 2000 and 2010, the total population grew by 20.6%, but Hispanics and Latino Americans grew by 65%, whereas non-Hispanic Whites grew by only 4.2%.[224] Texas has the fifth highest rate of teenage births in the nation and a plurality of these are to Hispanics or Latinos.[225][226] As of 2022, Hispanics and Latinos of any race replaced the non-Hispanic White population as the largest share of the state's population.[227]

Texas has the second-largest share of Mexican Americans in the US, making up 32.2% of the total population and 80% of the state's Hispanic population.[228] Other than Mexican, the largest self-reported ancestries in the state as of 2022 were German (8.1%), English (7.9%), Irish (5.8%), those identifying as American (4.6%), Italian (1.9%), Indian (1.9%), Salvadoran (1.4%), Scottish (1.3%), Vietnamese (1.1%), Chinese (1%), Puerto Rican (0.9%), Polish (0.9%), Honduran (0.8%), Filipino (0.8%), and Scotch-Irish (0.7%).[229][230][228]

Languages

[edit]

Main article: Languages of Texas

Most common non-English languages

| Language |

Population

(as of 2010)[231] |

| Spanish |

29.2% |

| Vietnamese |

0.8% |

| Chinese |

0.6% |

| German |

0.3% |

| Tagalog |

0.3% |

| French |

0.3% |

| Korean and Urdu (tied) |

0.2% |

| Hindi |

0.2% |

| Arabic |

0.2% |

| Niger-Congo languages |

0.2% |

The most common accent or dialect spoken by natives throughout Texas is sometimes referred to as Texan English, itself a sub-variety of a broader category of American English known as Southern American English.[232][233] Creole language is spoken in some parts of East Texas.[234] In some areas of the state—particularly in the large cities—Western American English and General American English, is increasingly common. Chicano English—due to a growing Hispanic population—is widespread in South Texas, while African-American English is especially notable in historically minority areas of urban Texas.

At the 2020 American Community Survey's estimates, 64.9% of the population spoke only English, while 35.1% spoke a language other than English.[235] Roughly 30% of the total population spoke Spanish. By 2021, approximately 50,546 Texans spoke French or a French-based creole language. German and other West Germanic languages were spoken by 49,565 residents; Russian, Polish, and other Slavic languages by 37,444; Korean by 31,673; Chinese 86,370; Vietnamese 92,410; Tagalog 40,124; and Arabic by 47,170 Texans.[236]

At the census of 2010, 65.8% (14,740,304) of Texas residents age 5 and older spoke only English at home, while 29.2% (6,543,702) spoke Spanish, 0.8 percent (168,886) Vietnamese, and Chinese (which includes Cantonese and Mandarin) was spoken by 0.6% (122,921) of the population over five.[231] Other languages spoken include German (including Texas German) by 0.3% (73,137), Tagalog with 0.3% (64,272) speakers, and French (including Cajun French) was spoken by 0.3% (55,773) of Texans.[231] Reportedly, Cherokee is the most widely spoken Native American language in Texas.[237] In total, 34.2% (7,660,406) of Texas's population aged five and older spoke a language at home other than English as of 2006.[231]

Religion

[edit]

See also: List of cathedrals in Texas

| Religious affiliation (2020)[238] |

| |

|

|

| Christian |

|

75.5% |

| Catholic |

|

28% |

| Protestant |

|

47% |

| Other Christian |

|

0.5% |

| Unaffiliated |

|

20% |

| Jewish |

|

1% |

| Muslim |

|

1% |

| Buddhist |

|

1% |

| Other faiths |

|

5% |

With the coming of Spanish Catholic and American Protestant missionary societies,[239] Indigenous American Indian religions and spiritual traditions dwindled. Since then, colonial and present-day Texas has become a predominantly Christian state, with 75.5% of the population identifying as such according to the Public Religion Research Institute in 2020.[240]

St. Mary's Cathedral Basilica of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston

St. Mary's Cathedral Basilica of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston

Among its majority Christian populace, the largest Christian denomination as of 2014 has been the Catholic Church, per the Pew Research Center at 23% of the population, although Protestants collectively constituted 50% of the Christian population in 2014;[241] in the 2020 study by the Public Religion Research Institute, the Catholic Church's membership increased to encompassing 28% of the population identifying with a religious or spiritual belief.[240] At the 2020 Association of Religion Data Archives study, there were 5,905,142 Catholics in the state.[242] The largest Catholic jurisdictions in Texas are the Archdiocese of Galveston–Houston—the first and oldest Latin Church diocese in Texas[243]—the dioceses of Dallas and Fort Worth, and the Archdiocese of San Antonio.

First Baptist Church of Dallas

First Baptist Church of Dallas

Being part of the strongly, socially conservative Bible Belt,[244] Protestants as a whole declined to 47% of the population in the 2020 study by the Public Religion Research Institute. Predominantly-white Evangelical Protestantism declined to 14% of the Protestant Christian population. Mainline Protestants in contrast made up 15% of Protestant Texas. Hispanic or Latino American-dominated Protestant churches and historically Black or African American Protestantism grew to a collective 13% of the Protestant population.

Evangelical Protestants were 31% of the population in 2014, and Baptists were the largest Evangelical tradition (14%);[241] according to the 2014 study, they made up the second-largest Mainline Protestant group behind Methodists (4%). Nondenominational and interdenominational Protestant Christians were the second largest Evangelical group (7%) followed by Pentecostals (4%). The largest Evangelical Baptists in the state were the Southern Baptist Convention (9%) and independent Baptists (3%). The Assemblies of God USA was the largest Evangelical Pentecostal denomination in 2014. Among Mainline Protestants, the United Methodist Church was the largest denomination (4%) and the American Baptist Churches USA comprised the second-largest Mainline Protestant group (2%).

According to the Pew Research Center in 2014, the state's largest historically African American Christian denominations were the National Baptist Convention (USA) and the Church of God in Christ. Black Methodists and other Christians made up less than 1 percent each of the Christian demographic. Other Christians made up 1 percent of the total Christian population, and the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox formed less than 1 percent of the statewide Christian populace. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the largest nontrinitarian Christian group in Texas alongside the Jehovah's Witnesses.[241]

Among its Protestant population, the Association of Religion Data Archives in 2020 determined Southern Baptists numbered 3,319,962; non-denominational Protestants 2,405,786 (including Christian Churches and Churches of Christ, and the Churches of Christ altogether numbering 2,758,353); and United Methodists 938,399 as the most numerous Protestant groups in the state.[242] Baptists altogether (Southern Baptists, American Baptist Associates, American Baptists, Full Gospel Baptists, General Baptists, Free Will Baptists, National Baptists, National Baptists of America, National Missionary Baptists, National Primitive Baptists, and Progressive National Baptists) numbered 3,837,306; Methodists within United Methodism, the AME, AME Zion, CME, and the Free Methodist Church numbered 1,026,453 Texans.

The same study tabulated 425,038 Pentecostals spread among the Assemblies of God, Church of God (Cleveland), and Church of God in Christ. Nontrinitarian or Oneness Pentecostals numbered 7,042 between Bible Way Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ, COOLJC, and the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World. Other Christians, including the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox, numbered 55,329 altogether, and Episcopalians numbered 134,318, although the Anglican Catholic Church, Anglican Church in America, Anglican Church in North America, Anglican Province of America, and Holy Catholic Church Anglican Rite had a collective presence in 114 churches.[245]

Non-Christian faiths accounted for 4% of the religious population in 2014, and 5% in 2020 per the Pew Research Center and Public Religion Research Institute.[241][240] Adherents of many other religions reside predominantly in the urban centers of Texas. Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism were tied as the second largest religion as of 2014 and 2020. In 2014, 18% of the state's population were religiously unaffiliated. Of the unaffiliated in 2014, an estimated 2% were atheists and 3% agnostic; in 2020, the Public Religion Research Institute noted the largest non-Christian groups were the irreligious (20%), Judaism (1%), Islam (1%), Buddhism (1%) and Hinduism, and other religions at less than 1 percent each.

In 1990, the Islamic population was about 140,000 with more recent figures putting the current number of Muslims between 350,000 and 400,000 as of 2012.[246] The Association of Religion Data Archives estimated there were 313,209 Muslims as of 2020.[242] Texas is the fifth-largest Muslim-populated state as of 2014.[247] The Jewish population was around 128,000 in 2008.[248] In 2020, the Jewish population grew to over 176,000.[249] According to ARDA's 2020 study, there were 43 Chabad synagogues; 17,513 Conservative Jews; 8,110 Orthodox Jews; and 31,378 Reform Jews. Around 146,000 adherents of religions such as Hinduism and Sikhism lived in Texas as of 2004.[250] By 2020, there were 112,153 Hindus and 20 Sikh gurdwaras; 60,882 Texans adhered to Buddhism.

Economy

[edit]

Main article: Economy of Texas

See also: Texas locations by per capita income and Texas Stock Exchange

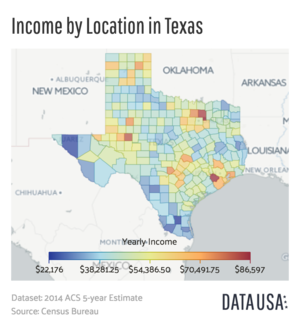

A geomap depicting income by county as of 2014

A geomap depicting income by county as of 2014

Texas counties by GDP (2021)

Texas counties by GDP (2021)

As of 2024, Texas had a gross state product (GSP) of $2.664 trillion, the second highest of any U.S. state.[251] Its GSP is greater than the GDP of Brazil, the world's 8th-largest economy.[252] The state ranks 22nd among U.S. states with a median household income of $64,034, while the poverty rate is 14.2%, making Texas the state with 14th highest poverty rate (compared to 13.15% nationally). Texas's economy is the second-largest of any country subdivision globally, behind California.

Texas's large population, an abundance of natural resources, thriving cities and leading centers of higher education have contributed to a large and diverse economy. Since oil was discovered, the state's economy has reflected the state of the petroleum industry. In recent times, urban centers of the state have increased in size, containing two-thirds of the population in 2005. The state's economic growth has led to urban sprawl and its associated symptoms.[253]

In May 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the state's unemployment rate was 13 percent.[254]

In 2010, Site Selection Magazine ranked Texas as the most business-friendly state, in part because of the state's three-billion-dollar Texas Enterprise Fund.[255] As of 2024, it has the second-highest number (52) of Fortune 500 companies headquartered in the United States.[256] In 2010, there were 346,000 millionaires in Texas, the second-largest population of millionaires in the nation.[f][257] In 2018, the number of millionaire households increased to 566,578.[258]

Taxation

[edit]

Texas has a reputation for a low tax.[259] According to the Tax Foundation, Texans' state and local tax burdens are seventh-lowest nationally; state and local taxes cost $3,580 per capita, or 8.4 percent of resident incomes.[260] Texas is one of seven states that lack a state income tax.[260][261]

Instead, the state collects revenue from property taxes (though these are collected at the county, city, and school district level; Texas has a state constitutional prohibition against a state property tax) and sales taxes. The state sales tax rate is 6.25 percent,[260][262] but local taxing jurisdictions (cities, counties, special purpose districts, and transit authorities) may also impose sales and use tax up to 2 percent for a total maximum combined rate of 8.25 percent.[263]

Texas is a "tax donor state"; in 2005, for every dollar Texans paid to the federal government in federal income taxes, the state got back about $0.94 in benefits.[260] To attract business, Texas has incentive programs worth $19 billion per year (2012); more than any other U.S. state.[264][265]

Agriculture and mining

[edit]

Cotton modules after harvest in West Texas

Cotton modules after harvest in West Texas

Texas longhorn cattle in Boerne, Texas

Texas longhorn cattle in Boerne, Texas

Texas has the most farms and the highest acreage in the United States. The state is ranked No. 1 for revenue generated from total livestock and livestock products. It is ranked No. 2 for total agricultural revenue, behind California.[266] At $7.4 billion or 56.7 percent of Texas's annual agricultural cash receipts, beef cattle production represents the largest single segment of Texas agriculture. This is followed by cotton at $1.9 billion (14.6 percent), greenhouse/nursery at $1.5 billion (11.4 percent), broiler chickens at $1.3 billion (10 percent), and dairy products at $947 million (7.3 percent).[267]

Texas leads the nation in the production of cattle, horses, sheep, goats, wool, mohair and hay.[267] The state also leads the nation in production of cotton which is the number one crop grown in the state in terms of value.[266][268][269] The state grows significant amounts of cereal crops and produce.[266] Texas has a large commercial fishing industry. With mineral resources, Texas leads in creating cement, crushed stone, lime, salt, sand and gravel.[266] Texas throughout the 21st century has been hammered by drought, costing the state billions of dollars in livestock and crops.[270]

Energy

[edit]

Main article: Energy in Texas

See also: Deregulation of the Texas electricity market

An oil well

An oil well

Brazos Wind Farm

Brazos Wind Farm

Ever since the discovery of oil at Spindletop, energy has been a dominant force politically and economically within the state.[271] If Texas were its own country it would be the sixth-largest oil producer in the world according to a 2014 study.[272]

The Railroad Commission of Texas regulates the state's oil and gas industry, gas utilities, pipeline safety, safety in the liquefied petroleum gas industry, and surface coal and uranium mining. Until the 1970s, the commission controlled the price of petroleum because of its ability to regulate Texas's oil reserves. The founders of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) used the Texas agency as one of their models for petroleum price control.[273]

As of January 1, 2021, Texas has proved recoverable petroleum reserves of about 15.6 billion barrels (2.48×109 m3) of crude oil (44% of the known U.S. reserves) and 9.5 billion barrels (1.51×109 m3) of natural gas liquids.[274][275] The state's refineries can process 5.95 million barrels (946,000 m3) of oil a day.[274][275] The Port Arthur Refinery in Southeast Texas is the largest refinery in the U.S.[274] Texas is also a leader in natural gas production at 28.8 billion cubic feet (820,000,000 m3) per day, some 32% of the nation's production.[276] Texas has 102.4 trillion cubic feet (2.90×1012 m3) of gas reserves which is 23% of the nation's gas reserves.[274][275] Many petroleum companies are based in Texas such as: ConocoPhillips,[277] EOG Resources, ExxonMobil,[278] Halliburton,[279] Hilcorp, Marathon Oil,[280] Occidental Petroleum,[281] Valero Energy,[282] and Western Refining.[283]

According to the Energy Information Administration, Texans consume, on average, the fifth most energy (of all types) in the nation per capita and as a whole, following behind Wyoming, Alaska, Louisiana, North Dakota, and Iowa.[274]

Unlike the rest of the nation, most of Texas is on its own alternating current power grid, the Texas Interconnection. Texas has a deregulated electric service. Texas leads the nation in total net electricity production, generating 437,236 MWh in 2014, 89% more MWh than Florida, which ranked second.[284][285]

The state is a leader in renewable energy commercialization; it produces the most wind power in the nation.[274][286] In 2014, 10.6% of the electricity consumed in Texas came from wind turbines.[287] The Roscoe Wind Farm in Roscoe, Texas, is one of the world's largest wind farms with a 781.5 megawatt (MW) capacity.[288] The Energy Information Administration states the state's large agriculture and forestry industries could give Texas an enormous amount of biomass for use in biofuels. The state also has the highest solar power potential for development in the U.S.[274]

Technology

[edit]

Astronaut training at the Johnson Space Center in Houston

Astronaut training at the Johnson Space Center in Houston

With large universities systems coupled with initiatives like the Texas Enterprise Fund and the Texas Emerging Technology Fund, a wide array of different high tech industries have developed in Texas. The Austin area is nicknamed the "Silicon Hills" and the north Dallas area the "Silicon Prairie". Many high-tech companies are located in or have their headquarters in Texas (and Austin in particular), including Dell, Inc.,[289] Borland,[290] Forcepoint,[291] Indeed.com,[292] Texas Instruments,[293] Perot Systems,[294] Rackspace and AT&T.[295][296][297]

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (NASA JSC) is located in Southeast Houston. Both SpaceX and Blue Origin have their test facilities in Texas.[298][299] Fort Worth hosts both Lockheed Martin's Aeronautics division and Bell Helicopter Textron.[300][301] Lockheed builds the F-16 Fighting Falcon, the largest Western fighter program, and its successor, the F-35 Lightning II in Fort Worth.[302]

Commerce

[edit]

Texas's affluence stimulates a strong commercial sector consisting of retail, wholesale, banking and insurance, and construction industries. Examples of Fortune 500 companies not based on Texas traditional industries are AT&T, Kimberly-Clark, Blockbuster, J. C. Penney, Whole Foods Market, and Tenet Healthcare.[303]

Nationally, the Dallas–Fort Worth area, home to the second shopping mall in the United States, has the most shopping malls per capita of any American metropolitan statistical area.[304]

Mexico, the state's largest trading partner, imports a third of the state's exports because of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). NAFTA has encouraged the formation of maquiladoras on the Texas–Mexico border.[305]

Transportation

[edit]

Main article: Transportation in Texas

The High Five Interchange in Dallas

The High Five Interchange in Dallas

The state's large size and rough terrain have historically complicated transportation. Texas has compensated by building the nation's largest highway and railway systems. The regulatory authority, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), maintains the state's highway system, regulates aviation,[306] and public transportation systems.[307]

The state is an important transportation hub. From the Dallas/Fort Worth area, trucks can reach 93 percent of the nation's population within 48 hours, and 37 percent within 24 hours.[308] Texas has 33 foreign trade zones (FTZ), the most in the nation.[309] In 2004, a combined total of $298 billion of goods passed through Texas FTZs.[309]

Highways

[edit]

Main article: Texas state highways

"Welcome to Texas" sign, entering the state from Arkansas on Interstate 30

"Welcome to Texas" sign, entering the state from Arkansas on Interstate 30

The first Texas freeway was the Gulf Freeway opened in 1948 in Houston.[310] As of 2005, 79,535 miles (127,999 km) of public highway crisscrossed Texas (up from 71,000 miles or 114,000 km in 1984).[citation needed] To fund recent growth in the state highways, Texas has 17 toll roads with several additional tollways proposed.[311] In Central Texas, the southern section of the State Highway 130 toll road has a speed limit of 85 miles per hour (137 km/h), the highest in the nation.[312] All federal and state highways in Texas are paved.

Airports

[edit]

See also: List of airports in Texas

Terminal D at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport

Terminal D at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport

Terminal E at George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston

Terminal E at George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston